[Music]

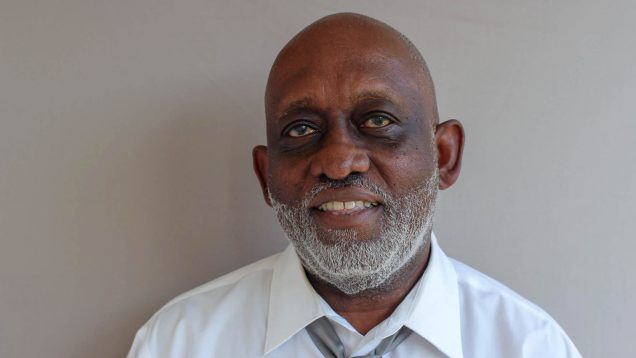

Jasmyn Morris (JM): In the fall of 1964, William Lynn Weaver, along with more than a dozen other black students, integrated West High School in Knoxville, Tennessee…

William Lynn Weaver (WLW): I don’t remember a day that a teacher did not tell me that I didn’t belong…

The school’s mascot was a Confederate colonel and, at football games, there were always racial comments, banners with the n-word.

I remember the last day I had class at West walking out the door, and I consciously refused to look back.

JM: …That is…until now….

WLW: We’re going to West High School…And, uh, it’s momentous for me because I’ve never even driven past the school in fifty years. And now, here I am, headed back to West.

GPS: Prepare to turn right in half a mile…

JM: On this season of the StoryCorps podcast from NPR…we’re bringing you stories of reunions…

I’m Jasmyn Morris. Stay with us….

[Sponsor]

JM: Welcome back… If you listen to StoryCorps on NPR’s Morning Edition each week… you may recognize the voice of William Lynn Weaver — who goes by Lynn.

He’s a bit of a celebrity here at StoryCorps — he actually holds the record for the most StoryCorps broadcasts — and embodies the very heart of our mission: to speak openly and listen closely. He’s shared a lot stories with us over the years — about growing up in the civil rights era-south, about his career in medicine, and some about family.

Here’s Lynn in his very first StoryCorps recording…

WLW: My father was everything to me. And it’s actually kind of difficult talking about him without becoming very emotional. Up until, you know, he died, every decision I made, I’d always call him. And he would never tell me what to do, but he would always listen and he made me feel that I could do anything that I wanted to. I can remember when we integrated the schools, that, there were many times when I was just scared, and I didn’t think that I would survive, and I’d look up and he’d be there.

JM: In that first interview from 2007, Lynn briefly mentioned integrating his high school in the late 60s… He was 14 at the time and about to start his sophomore year at West… a previously all-white High School in Knoxville, Tennessee…

And at StoryCorps, Lynn sat down for a separate interview, to tell the full story…

WLW: As soon as we got into the school, the principal was calling the roll. He said, ’Bill Weaver,’ and I said, ’My name is William.’ And he said, ’Oh, you’re a smart n-word.’ I’d been in school maybe thirty minutes and he suspended me.

I don’t remember a day that a teacher did not tell me that I didn’t belong. We’d have a test and they’d stand over me and then just snatch the paper out from under and say, ‘Time’s up.’

The first report card I got all Fs, including Phys. Ed. So I’ve gone from being a good student to starting to think, ‘Well, maybe I don’t belong; maybe I am dumb.’

I was home one evening wondering what I’m going to do when there’s a knock on the door, and it’s my seventh grade science teacher from the black school, Mr. Hill. He said, ‘You know, I understand that you’re having some trouble.’ And I said, ‘Yeah, Mr. Hill. I think they’re trying to run me away.’ And he said, ‘What I need you to do is to come back to the junior high school after school, every day and Saturday mornings.’ He said, ‘Can you do that?’ I said, ‘Yes, Sir.’

And so every day waiting for me would be Mr. Hill with assorted other teachers — the English teacher, the math teacher — and they tutored me. And once I got past those Fs, I stopped doubting myself but learning became almost a spiteful activity to prove the teachers at the high school wrong. And no matter what I did academically, I was never recognized at that school.

JM: The disrespect and harassment that started in the classroom also followed Lynn onto the football field…

More on that after this short break…

Stay with us…

[Sponsor]

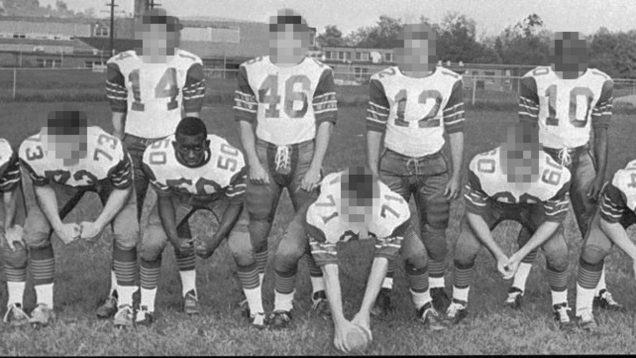

JM: In addition to integrating West, Lynn and several other black students (including his older brother) also integrated the school’s football team.

Here he is again, describing what it was like playing for the West High School Rebels…

WLW: The school’s mascot was a Confederate colonel and at football games, when you came out on the field, the crowd would be hollering and the Dixie would be playing and they’d hold the paper flag up and the team would burst out through the Confederate flag. The black players made a decision to run around the flag.

We had teams who refused to play us because we had black players. There were always racial comments, uh, banners with the n-word, and, at one point in time, there was even a dummy with a noose around its neck hanging from the goal posts.

I remember we played an all-white school. The game was maybe only in the second quarter. My brother tackled their tight end and broke his collarbone. And, when they had to take him off the field with his arm in a sling, that’s when the crowd really got ugly.

We were on the visitors’ sideline and they were coming across the field; so we backed up against the fence. I remember the coach saying, “Keep your helmet on,” so I was pretty afraid. And then a hand reaches through the fence and grabs my shoulder pads. I look around and it’s my father. And I turned to my brother, I said, “It’s okay. Dad is here.”

The state police came and escorted us to the buses. The crowd is still chanting and throwing things at the bus and, as the bus drives off, I look back and I see my father standing there and all these angry white people. And I said to my brother, “How’s Daddy going to get out of here? They might kill him.”

We get to the high school and the most incredible feeling I think I’ve ever had was when my father walked through the door of the locker room and said, “Are you ready to go?” As if nothing had happened. And I wanted to tell him, “Dad, don’t come to any more games,” but selfishly I couldn’t. I needed him there for me to feel safe.

Normally when you’re with a team you feel like everybody’s going to stand together; and I never got that feeling that the team would stand with me if things got bad. I think a number of the white students who were there with me would say now, If I could have did something different, I would’ve said something. But that’s what evil depends on, good people to be quiet.

[Music]

JM: Lynn graduated from West High School in 1967. He took his diploma, left Knoxville, and never looked back.

He went on to have a long career in medicine … performing and teaching surgery at hospitals and universities across the country. He’s now Chief of Surgery at the Fayetteville North Carolina VA Medical Center… and will be retiring this week.

…And we asked Lynn if he had any regrets about going to West.

WLW: Boy, that’s a difficult question. I think West defined me and, once I finished West, I said, ”Okay, I can finish college; I can do medical school because I’ve been through worse… But I have PTSD from West High School.

In the 50 years since I graduated, I’ve never even driven by West High School. So I don’t regret it but I can’t let it go. I’ve come away with a lot of scars.”

JM: For Lynn… these StoryCorps interviews have been part of his healing process… and after his stories about integrating West aired on NPR last year… he got hundreds of responses from listeners thanking him for sharing what he went through… but there was one in particular that caught his attention…

For more on that message and how it led to an unexpected high school reunion 50 years later … tune in next week.

This episode was produced by Jud Esty-Kendall and me. Thanks to our engineer David Herman…and script editors Danielle Roth and Sylvie Lubow.

If you want to leave a voicemail for Lynn, give us a call at 301 744 TALK.

To find out what music we used in this episode and to sign up for your own interview… visit our website, www.storycorps.org.

For the StoryCorps podcast, I’m Jasmyn Morris. Thanks for listening.

[Music + Promo]