NARRATOR(N), MATTEW KENNEDY(MK), DAVID ISAY(DI), WALTER WILLIAMS(WW), JOHN DORMAN(JD), SOL SEIDERMAN(SS), SOL GABER(SG) and CUSTOMER(C)

N: It was once said that if Paris is France, then Coney Island between June and September is the world. In its heyday — at the beginning of this century — Brooklyn’s Coney Island was the world’s pleasure palace. It had three of the most spectacular amusement parks ever built. There was Steeplechase Park, where customers raced mechanical horses along miles of track, glittering Luna Park, lit-up by more than a million lights, offering among other treats a simulated trip to the moon. Dreamland was bigger and more spectacular still, featuring Liliputia, a miniature metropolis.

But in 1911, when Dreamland burned to the ground, Coney Island began its slow descent. Today what was once Luna Park is now the Luna Park Housing Projects. Steeplechase Park is a vacant lot. The once great Half Moon Hotel is now a geriatric center.

But, as producer David Isay has discovered, there are still a few relics of the days when Coney Island was the world.

MK: (talking on phone): ”Coney Island Chamber of Commerce . . . No, Steeplechase Park closed in 1964. Thank you very much.”

MK: Welcome to marvelous Coney Island. My name is Mathew Kennedy. I’ve been with the Chamber of Commerce here since 1924.

DI: Out of a tiny second story office on Surf Avenue, 86 year-old Matt Kennedy has run the Coney Island Chamber of Commerce by himself for decades. It’s not a fancy operation. There’s a desk, a file cabinet, an old royal manual typewriter. On the walls hang a few ancient Coney Island photos which shake along with the rest of the office each time another subway train rumbles by on the elevated tracks just outside his window.

(Subway horn blows.)

(Phone rings)

MK: Coney Island Chamber of Commerce.

DI: During the summer months, the chamber’s rotary phone rings off the hook. Today, most of the calls come from nostalgic retirees down in Florida, just checking in on old Coney Island. Matt Kennedy, a cigar perpetually clenched between his fingers, fields each call happily.

MK: People call and they want to know the temperature of the water. I ask them to wait a moment and I’ll go down and see. Then I go out and take a wiz and come back and tell them 60 degrees or 70 or 68 or whatever number comes to mind, and they seem to be satisfied and thank me.

(Phone Rings)

MK: ”Yes? Of course Coney Island still exists. Right. It’s bigger and better than ever. Thank you very much.”

DI: Despite the fact that today’s Coney Island may look like little more than a dingy five-block long stretch of rundown amusements, disco bumper cars, and video arcades, Matt Kennedy has made it his mission to let the world know that there’s a lot more to Coney Island than meets the eye.

(Music starts.)

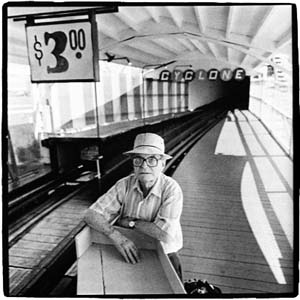

MK: Right across the street from my office stands the Cyclone roller coaster, which opened in 1927. It’s the largest, fastest, and most thrilling ride in the world. The Cyclone is a monument comparable only to the Eiffel Tower.

(Sounds of hammering.)

DI: Each morning, as dawn starts to break over a sleeping Coney Island, Walter Williams, the caretaker of the Cyclone roller coaster, begins his day of work. Slowly but skillfully, he starts to climb the first steep hill of the Cyclone, tapping every inch of steel track with a hammer to check for loose nuts and screws, eyeing the creaky structure for rotting wood.

WW: These two screws here, see they loose.

DI: The daily three-hour journey up and down and around the mile of Cyclone track might seem like a lot for this gray-haired 53 year-old, but Walter Williams doesn’t seem to mind.

WW: I take of her, I see after her. I fix her, and I make sure she’s okay. I love the cyclone, like you would love your wife.

DI: The Cyclone is the last working roller coaster on Coney Island, where the world’s first roller coaster, ”The Thompson Switchback Railway,” was built in 1884. Despite it’s 60 years, the Cyclone is still considered, by those who know these things, to be the greatest in the world

Each day at noon, the padlocked gates to the cyclone are swung open and anxious customers stream in to board the roller coaster’s three ancient cars. An old sign exhorts them to ’hold onto their wigs,’ as a pot-bellied, tattooed attendant locks them in for the ride of their lives.

(Sounds of children on ride.)

Moments later, the brakes are released, and a chain hauls the cars, groaning and creaking, ever so achingly slowly up an enormous hill. At the top, for that brief instant, the world freezes, the heart stops as the view of that terrifying straight-down endless drop comes into focus. Then it happens.

(Sound of screaming.)

From there on in the ride, propelled only now by gravity, doesn’t slow for an instant.

WW: The ride is about a minute and forty seconds of fun, of natural fun.

DI: Walter Williams spends most of his afternoons leaning back against his tool shed at the center of the Cyclone, watching as the cars flies by.

WW: It goes up a hill, it goes down a hill, it goes up a camel back, it goes up a big hill, it goes down another hill, up another camel back, ’round a curve, back into the station.

Sometime, when peoples get off the roller coaster they throw up, they be shaking, and sometime they just fall, like something hit ’em, like they died. They just lay there, they eyes closed. It’s a hell of a ride to be on.

DI: It’s a ride with history. There was Charles Lindbergh, who, soon after his solo flight across the Atlantic, rode the Cyclone and called it the thrill of his life. Then there was the army private left mute by battle trauma during World War II. He was unable to speak for five years, until after taking a ride on this roller coaster, he stood up weak kneed and uttered his first words: ”I feel sick.”

And even though the decrepit Cyclone may seem to bend and strain and shudder through each screeching ride it gives, even though it may look like it’s got one leg in roller coaster heaven, if you bother to ask Walter Williams, the roller coaster man, he’ll tell you that he knows better.

WW: The Cyclone will stand forever. It will be here as long as peoples is here. And as long as peoples is here, I feel though that the world will be here, and as the world is here I think that the Cyclone will be here too, as long as it has someone to take care of it the way that I do.

(”Coney Island Baby” fades in.)

MK: Coney Island has always meant sweets. Everything from the Eskimo Pie to Saltwater Taffy was invented here. There was once a dozen candy stores operating up and down Surf Avenue. Today, the only one remaining here is Coney Island’s first — Phillip’s Candy.

DI: Right down the block from Matt Kennedy and the Chamber of Commerce, in the ramshackle old subway station, stands an unlikely sight — a tiny walk-up shop, freshly painted in red and white stripes.

JD: Alright, who’s next, who’s next? Fresh made, we got ’em.

DI: The store’s showcase windows are piled high with caramel apples and coconut patties, walnut maple fudge, and huge swirled lollipops on sticks as large as baseball bats. This is Philip’s Candy.

(Sounds of the candy shop.)

Behind the counter stands an unshaven gray-haired man in a perpetually stained white jacket. John Dorman, who owns the store, has worked here since 1947.

JD: There are some candy shops that make fudge, or they make chocolates, or they make taffies. But this candy shop makes everything and we make it from scratch.

DI: And if you stand on tiptoes and peer over the antique cash register, around the jars and trays of candy, you can almost make out where it all happens. Cramped into the back room at Philip’s is an entire candy factory, run day and night by Dorman and his small staff. It’s hot, and the sickeningly sweet smell is overpowering. A worker sticks an enormous wooden spoon into a cast-iron cauldron filled with something sticky and blue. Right next to her, a rotating belt-driven contraption pours out a never-ending stream of popcorn. Cotton candy hangs on a crisscross of clothes lines overhead as the wheels and gears of a fire-truck red taffy machine spit out 145 pieces a minute.

JD: We make a coconut cream bar, which is chops of coconuts in cream, and then we dip the whole thing in chocolate. We make the cashew balls — that’s a marshmallow dipped in caramel, and then we roll them in cashews, or walnuts, or pecans. We make a chop suey, which is coconut brittle, with nuts and raisins. And the list goes on and on and on. It never stops.

DI: The only thing that has seemed to stop at Philip’s Candies is time. The recipes haven’t changed here at all since Philip Calamaris opened the store in 1907. An old photograph in the window, dated 1930, shows that the store even looks exactly the same as it did during Coney Island’s glory days.

JD: That’s two, three, four, five is ten, ten is twenty. Have a good weekend, eh? Thank you.

DI: And proprietor John Dorman? He still sticks by the true candyman’s credo.

JD: This is the place for good stuff. The best. You come here, we’re gonna make you happy. If we don’t make you happy, we’ll keep working on you until we find something that will make you happy. You’re not gonna leave Phillip’s Candies until you are happy.

(Song fades in.)

MK: Just across the street from Philip’s Candies stands the original Nathan’s Famous Hot Dogs stand. I remember well that historic day in 1916 when Nathan Hanwerker and his wife Ida opened Nathan’s. Today, thanks to them, the hot dog is an American tradition.

DI: There have always been are two ways to buy a frank at Nathan’s Famous Hot Dog stand. Most people line up at the long chrome counters on Surf Avenue and pick up a dog to go.

(Sounds of hot dog stand.)

But if you’re looking for a more personal touch, you can venture down the narrow alley to the side of the stand, through two swinging doors into Nathan’s famous dining room. There you’re in safe hands.

SS: My name is Sol Seiderman.

SG: My name is Sol Gaber.

SS: We’ve been working as waiters for Nathan’s for the past forty years.

DI: Sol and Sol, gray haired and paunched, in matching yellow and black Nathan’s uniforms, work the day shift in the dining room as they have for decades.

SG: When people come in they think that Sol and Sol are brothers. It’s just like a husband and wife, after they been married for many years that they start to look like each other. And the same thing with us.

DI: The dining room is small and drab and hot. There are a dozen tables and a single booth, which Sol and Sol reserve for lovebirds. Round portholes filled with yellow-tinted plastic serve as windows. It’s not unusual to find a cockroach or two strolling across the floor.

SG: It doesn’t look like a fancy restaurant in a sense like you’re going to a really fancy restaurant, but the atmosphere.

SS: You come in here and you’re comfortable, nothing special here. We don’t decorate the place for you.

SG: You feel at home when you come to Nathan’s dining room. You feel at home more than if you go to what you call a beautiful place, and that’s the whole thing.

SG: Sol can you pick up sixteen franks for me please, two orders of French-fries and four cokes.

SS: Okay Sol, sixteen franks, four orders of French-fries . . .

DI: The frank was invented on Coney Island in 1896 by an immigrant from Frankfurt, Germany named Alfred Feltman, who owned the great Feltman’s Restaurant. One of his employees was an enterprising young bun-slicer named Nathan Hanwerker, who knew a good thing when he saw one. Hanwerker quit Feltman’s, borrowed $300, opened up this stand, and called his product the hot dog. It caught on and Nathan’s became an American institution.

SG: You’d be amazed at some of the biggest movie stars that you think would go to the finest restaurant, and yet they wind up at Nathan’s eating a hotdog.

SS: I’ve served personally Marilyn Monroe, Doris Day, Edward G. Robinson.

SG: I never dreamt in my life that Sol would meet people like that.

DI: And while people like that may no longer be coming to Nathan’s dining room, Sol and Sol still have their hands full with customers.

SS: How do you do ladies?

DI: The routine is simple. Sol and Sol sit their patrons down at a table, point to the large menu hanging on the wall, and take the order.

SG: Ma’am, listen to me, it comes out cheaper for you. It’s a special, honestly. I want to explain it to you.

DI: After getting everything straight, Sol (or Sol) heads to the back of the kitchen where that order is announced into an ancient squawk box attached to the wall.

SS: Attention please, attention. Give me fourteen franks, four orders of French-fries with cheese, two with . . .

DI: Then, in a flash it’s back to the table, a tray of piping hot hotdogs in hand.

SG: There’s nothing like Nathan’s franks. It’s 100% beef. And I mean entirely 100% beef, in other words there’s no mixture in there. And the taste of the frank is really, it’s very hard to describe, but it’s so delicious.

SS: We serve a skin hotdog, which is much better than the skinless hotdog. So when you eat the hotdog it actually cracks in your mouth.

SG: Ninety-nine percent of the people that come here don’t put nothing at all on the franks except mustard. Because people want to really get the taste of the frank.

SG: We don’t have sauerkraut ma’am.

C: What do you mean you don’t have sauerkraut?

SG: Ma’am, listen to me. If you have sauerkraut on a frank you could eat any frank. You wouldn’t know the difference. This way you taste it.

DI: A lot’s changed since Sol and Sol started working here in the early nineteen fifties. The price of a hotdog has gone up from a nickel to $1.75. The lines for the dining room, which used to snake around the block on Saturdays and Sundays, have disappeared, as have the mobsters and politicians and stars. And now, at 72, the older of the two Sols, Sol Gaber, is finally ready to turn in his apron and retire.

SG: You know the funny about the whole thing is that all I am here is a waiter. And yet I’m proud. I’m proud of the fact that I work here. I’ve served here families that came in with children, and then I served the children that came in with their own families. And of course when I retire, I certainly will miss it. And I’ll miss Sol.

DI: But for now, if you hurry, you can still catch Sol and Sol at Nathan’s dining room, serving up their little bit of hotdog heaven.

SS: Bye-bye.

SG: Take care, bye-bye, hope you call again.

(”Under the Boardwalk” fades in.)

MK: Well, I certainly hoped you’ve enjoyed your visit to Coney Island. If you’re ever close by, stop in and see us. We’ll be here. I’m Matt Kennedy, from the Coney Island Chamber of Commerce.