The Rise of Yiddish Swing

Yiddish swing. Jazz and klezmer. It may sound like an odd combination, but in late 1937 this mix of Old World and New took the music scene here and abroad by storm. The fad got its start when the Andrews Sisters, a young three-sibling act fresh from Minnesota, recorded an irresistible swing version of a forgotten Yiddish stage tune. “Bei Mir Bist du Schoen” (You Are Beautiful to Me) became an instantaneous hit, spawning an unending series of covers and, with them, a musical trend.

Within weeks, executives at New York’s WHN had created Yiddish Melodies in Swing, a weekly program dedicated to the new musical fusion. The talented pianist/composer Sam Medoff was hired to lead the show’s “Swingtet” and to arrange rollicking versions of traditional Jewish folk and klezmer tunes like “Dayenu,” “Eli Meylakh,” and “Yidl Mitn Fidl.”

Front and center on Medoff’s bandstand were the Barry Sisters (née Bagelman), whose close-as-air harmonies, spunky energy, and seamless transitions from Yiddish to English packed New York’s 600-seat Loews State Theater every Sunday at 1 p.m. But Yiddish Melodies didn’t just mainstream Yiddish culture, it reconnected a younger generation of American Jews to an older musical tradition embodied by the Swingtet’s legendary clarinetist, Dave Tarras, a European-born klezmer musician with almost no equal.

Yiddish Melodies in Swing lasted nearly two decades, outliving swing, the golden age of radio, and almost Yiddish culture itself. Small wonder that the 26 surviving episodes of the show are as fresh today as they were on the Sunday afternoons when they aired.

Claire Barry is the narrator of the Yiddish Radio Project episode about Yiddish swing. From almost two decades, Claire and her sister Myrna were the singing stars of the radio program Yiddish Melodies in Swing.

Paul Pincus, the co-narrator of the Yiddish Radio Project episode about Yiddish swing, is one of the only men alive to have shared the bandstand with both Dave Tarras and Naftule Brandwein, the two greatest klezmer clarinetists of the twentieth century.

The Barry Sisters and Jan Bart promoting the sponsors of Yiddish Melodies in Swing.

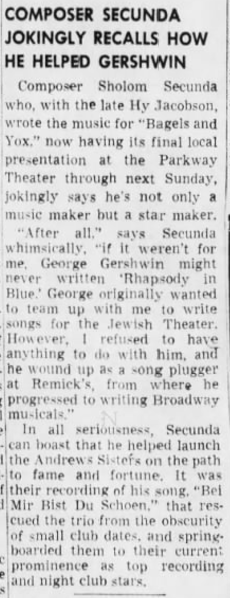

The Andrews Sisters pose with Sholom Secunda. The Andrews Sisters’ swing version of Sholom Secunda’s “Bei Mir Bist Du Schoen” launched the era of Yiddish swing.

Loews State Theater building, where 600 revelers showed up each week to see the broadcasting of Yiddish Melodies in Swing.

The disc label from one of the surviving Yiddish Melodies in Swing recordings.

Dave Tarras, the clarinetist on Yiddish Melodies in Swing.

Naftule Brandwein, the self-styled “King of Jewish Music” and Dave Tarras’s chief rival for the crown of the twentieth century’s greatest klezmer clarinetist, in a photo from the 1950s. Between 1924 and 1927, Brandwein recorded some twenty-four discs. But New World musical tastes gradually eclipsed Brandwein’s Old World playing style.

Peter Sokolow was Dave Tarras’s last keyboard player. The premier pianist and orchestrator of classic Jewish music, he is the musical director of the Yiddish Radio All-Star Band.

“Bei Mir Bist Du Schoen”

The story of this tune’s stratospheric rise is as unlikely as that of Yiddish swing itself. “Bei Mir Bist Du Schoen” was composed by Sholom Secunda for a 1932 Yiddish musical that opened and closed in one season. Fast-forward to 1937. Lyricist Sammy Cahn and pianist Lou Levy were catching a show at the Apollo Theater in Harlem when two black performers called Johnnie and George took the stage singing “Bei Mir Bist Du Schoen” — in Yiddish. The crowd went wild. Cahn and Levy couldn’t believe their ears. Sensing a hit, Cahn convinced his employer at Warner Music to purchase the rights to the song from the Kammen Brothers, the twin-team music entrepreneurs who had bought the tune from Secunda a few years back for the munificent sum of $30.

Cahn gave “Bei Mir” a set of fresh English lyrics and presented it to a trio of Lutheran sisters whose orchestra leader, oddly enough named Vic Schoen, had a notion of how to swing it. The Andrews Sisters’ debut 78 rpm for the Decca label hit almost immediately. The era of Yiddish swing had begun.

“Bei Mir” would soon be covered by virtually every pop and jazz artist of the age, and was even retranslated into French, Swedish, Russian — and German. (The song was a hit in Hitler’s Germany until the Nazi Party discovered that its composer was a Jew, and that the song’s title was Yiddish rather than a south German dialect.)

The song’s success also sparked frenzied searches for other Yiddish crossover hits. Some attempts, like “Joseph, Joseph” (“Yosl, Yosl”), by the team of Chaplin and Cahn for the Andrews, and “My Little Cousin” (“Di Grine Kuzine”), by Benny Goodman, found modest success. But no Yiddish song would ever hit it as big again.

Sammy Cahn claimed that he bought his mother a house with money earned from “Bei Mir.” For her part, the mother of Sholom Secunda visited the synagogue every day for a quarter century to ask God for forgiveness, certain that he was punishing her son for a sin she had committed.

Brooklyn Eagle, December 24, 1937

Brooklyn Eagle, August 24, 1952

Sholom Secunda originally composed “Bei Mir Bistu Du Schoen” for the Yiddish musical Men Ken Lebn Nor Men Lost Nisht (I Would If I Could), which opened and closed in one season.

The Barry Sisters were the Yiddish answer to the Andrews. Born Clara and Minnie Bagelman, they changed their names to Claire and Myrna, the Barry Sisters, the night they heard the Andrews Sisters’ version of “Bei Mir” on the radio.

Benny Goodman played “Bei Mir” at his historic Carnegie Hall concert in 1938.

Guy Lombardo’s version of “Bei Mir” was the third to hit number one in 1938, after the Andrews Sisters’ and Benny Goodman’s.

Leo Marjane covered “Bei Mir” in French. The song was soon to get Russian, German, and Swedish lyrics as well.

Tarras and Brandwein

Dave Tarras, the Yiddish Melodies in Swing clarinetist, was brought up in the world of klezmer, the traditional instrumental music of Eastern European Jews. But he was no stranger to the New World technology of radio.

Apart from his longstanding gig on Yiddish Melodies in Swing, Tarras was the musical director of the low-power WBBC (Brooklyn Broadcasting Company), where he played old-fashioned bulgars and sweet waltzes between programs, tailoring the name of his ensemble to whoever was footing the bill. His band could start the afternoon as Dave Tarras and the WBBC Ensemble, transform fifteen minutes later into Dave Tarras and the Breakstone Ensemble, and round out the hour as Dave Tarras and the Stanton Street Clothiers Ensemble.

Key to Tarras’s success were his extraordinary music reading ability and his capacity to show up to a gig sober and on time. Neither quality was shared by Tarras’s chief rival, Naftule Brandwein — the other leading contender for the title of the twentieth century’s greatest klezmer clarinetist.

Brandwein was Tarras’s opposite in almost every respect. Unable to read a note of music, he preferred the poker table to the bandstand and the liquor bottle to just about everything else. Onstage he wore an Uncle Sam outfit wrapped in Christmas lights, which blew up one night as his perspiration got out of hand. His playing was as rough and wild as his temperament, laced with elements of Greek, Turkish, and Gypsy music.

Brandwein was a fearless musician, always teetering on the edge of disaster. A favorite of Murder Incorporated, for whom he performed in a famed hideaway behind a Brooklyn candy store, the talented iconoclast left a lasting mark on the development of klezmer music.

Aficionados of the genre argue to this day about which of the two klezmer masters, Tarras or Brandwein, was the greatest. As far as who was better suited to radio, history long ago passed definitive judgment.

Naftule Brandwein, c. 1920.

By 1935, when this portrait was taken, Dave Tarras had been in the United States for 12 years, and was well-established in the New York music scene.

This documentary comes from Sound Portraits Productions, a mission-driven independent production company that was created by Dave Isay in 1994. Sound Portraits was the predecessor to StoryCorps and was dedicated to telling stories that brought neglected American voices to a national audience.